The Church

The Church of San Jacopo and San Filippo, dating back to the 12th century, has an important history linked to the religious and civic functions of Certaldo. It has undergone architectural modifications and restorations that have recovered its medieval appearance. Inside, there are significant works, such as the Crucifix of Petrognano and frescoes by Memmo di Filippuccio. The funerary monument of Giovanni Boccaccio and the altar of Blessed Giulia testify to the historical and artistic importance of the church.

Venue for civic and religious ceremonies since the 12th century

Origins of the Church

The church, which already existed in the 12th century, was originally dedicated to San Michele Arcangelo and San Jacopo and was the site for meetings to elect the procurators of the Community as well as, from 1415, ceremonies for the installation of the new vicar.

Associated with it were a hospital intended for the reception of wayfarers and the needy, still active in 1394, and the cemetery adjacent to the building.

Suffragan of the parish church of San Lazzaro in Lucardo under the patronage of the Gianfigliazzi family, thanks to the mediation of the Giandonati family of Certaldo, by papal bull in 1408 the church and its furnishings were handed over to a nucleus of monks attached to the convent of Santo Spirito in Florence, Augustinians who remained until the suppression of religious orders sanctioned in 1783 by Motu Proprio of Grand Duke Peter Leopold, who decreed the handing over of the church to the Archdiocese of Florence, which, by archiepiscopal decree of August 11, 1854, reunited it with the parish of San Tommaso.

Architectural features and restoration works

Architecture and Restorations

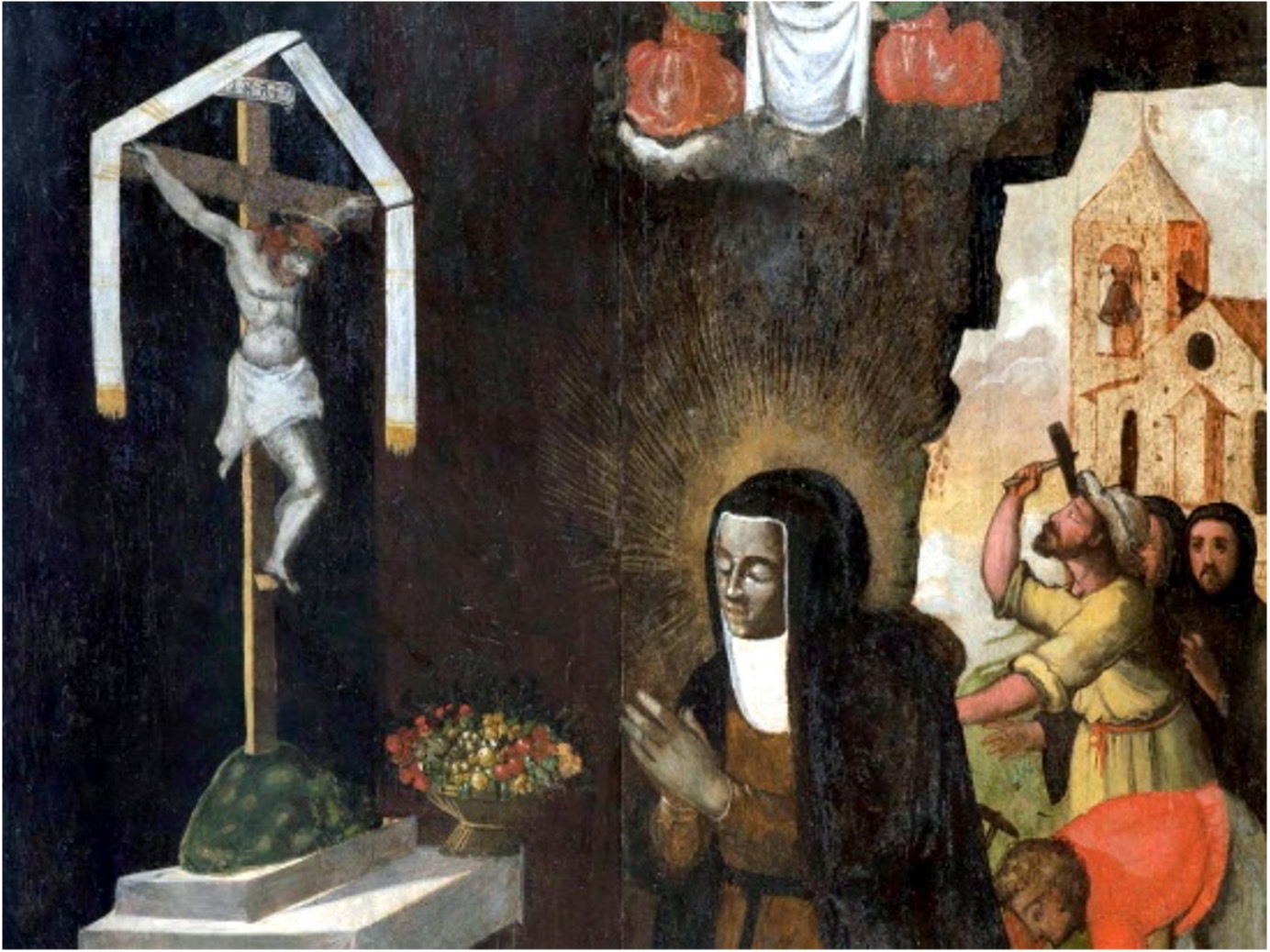

On the outside, the church has a simple gabled façade, flanked by the bell tower, which has a square plan with a cell provided with four arches with the same number of bells, ending in a spire reconstructed during the works of the twentieth century to restore its original form, similar to that which appears in the painting Beata Giulia praying in front of the Crucifix, placed in the church on the altar dedicated to the Certaldese blessed.

The bare appearance of the church’s interior, which has a single nave with a trussed ceiling and exposed brickwork, is the result of the architectural restoration initiated in 1963 by the Florentine Monuments Superintendency, which, in the name of recovering the building’s presumed original medieval appearance, according to the restoration method of the time, had the altars erected between the 16th and 18th centuries removed, the plaster with the neo-Gothic decoration removed, the apsidal fresco attributed by sources to Galileo Chini, and the original doors and the row of single-lancet windows restored.

Artistic heritage and historical memory

Art and Testimonies

Inside the church are preserved works of art of relevant interest, precious evidence of the union of faith and politics in the historical events of Certaldo. In the apse basin stands in all its solemnity the thirteenth-century Crucifix of Petrognano, a work that will be discussed in its dedicated card. Along the left aisle, to the side of the entrance counter-façade, within a niche, remains the valuable fresco depicting the Madonna between Saints Jacopo and Peter, with the kneeling patron who was never identified but who, over time, was wrongly believed to be Saint Verdiana. The work – discovered in 1861 and restored in 1995 – is the oldest pictorial evidence in the church, possibly the crowning of an altar or tomb, and has been attributed to the Sienese Memmo di Filippuccio (c. 1250-c. 1325), a civic painter in San Gimignano and father-in-law of Simone Martini. The spatial construction and the plastic prominence of the figures still reflect what the painter learned from Giotto in the great building site of the Basilica Superiore in Assisi, according to Roberto Longhi (1948), author of the half-figures of saints and prophets portrayed in the decorative bands of the Biblical Stories and collaborator in the drafting of the first panels of the Franciscan Stories.

On the same wall is the sepulchral monument of Giovanni Boccaccio accompanied by a bust of the poet, commissioned in 1503 by the vicar Lattanzio di Francesco Tedaldi from Giovan Francesco Rustici, a poet buried here in 1375 and moved to the cemetery in front of the convent following the Lorraine decree prohibiting church burials. Under the bust is the marble epigraph with dedication dictated by Coluccio Salutati. The exact location of Boccaccio’s burial is indicated by a marble tile placed on the floor, next to the tomb slab carved in neo-medieval style in 1952 by Mario Moschi, with the arms of the Boccaccio family and the municipality of Certaldo. The bas-relief effigy of the poet takes its cue from the portrait of the poet frescoed by Andrea del Castagno in the series of Illustrious Men at Villa Carducci in Legnaia (Florence), transferred after detachment to the Uffizi Gallery.

On this wall there was the entrance to the Chapel dedicated to Beata Giulia, which was opened during the works in the 1880s and then demolished in the 1960s to restore the Gothic forms of the church and recover the cloister, which was totally occupied by the room. Fortunately, the interior furnishings were preserved, with its majestic wooden altar and altarpiece, seats, candelabras and wooden carvings, all of which are now divided between the museum, convent storehouse and St. Thomas the Apostle Church.

Giovan Francesco Rustici, Funerary monument (left) and bust (right) of Giovanni Boccaccio

Terracotta tabernacles and the altar of Blessed Giulia

Tabernacles and Altars

On the walls on either side of the apse are two glazed terracotta tabernacles: on the left there is the one donated in 1499-1500 by the vicar of Certaldo Ludovico di Benintendi Pucci, attributed to Benedetto Buglioni, while on the right there is the one attributable to the workshop of Andrea della Robbia, donated in 1502-1503 by the vicar of Certaldo, Ristoro d’Antonio Serristori. The marble baptismal font dates back to 1572, employed instead as a stoup following the ban on baptisms promulgated in 1632-33 by the Florentine archdiocese to quell conflicts between the Augustinians and the Gianfigliazzi family.

Along the right aisle is the altar dedicated to Beata Giulia, documented from 1372 and renewed in 1633 as a sign of thanksgiving for the escape of the plague, an occasion to clothe the remains of the young tertiary with a sumptuous vestment, now on display in the cell, and to reunite with the skeleton the skull stolen by Aragonese troops during the sack of Certaldo in 1479 and returned seven years later by Ferdinand of Aragon thanks to the diplomatic mission of Giovanni Lanfredini, Florentine ambassador in Naples.

Glazed terracotta tabernacle attributed to Benedetto Buglioni (left), glazed terracotta tabernacle attributed to the workshop of Andrea Della Robbia (right)

The loss of the cusped dossal made specifically for the new altar, perhaps commissioned by Agnolo di Pierozzo Giandonati, prior of the rectory of Santi Michele e Jacopo, a friend of Boccaccio and the main promoter of Giulia’s cult, deprives us of the only evidence of a true portrait of the Beata in the habit of the Augustinian mantellate, flanked by two side compartments where the scenes of her death before the Crucifix and her funeral are illustrated, a narrative that has come down to us thanks to a watercolor drawing (Florence State Archives), executed in the seventeenth century when the panel was in the sacristy. Perhaps accompanying that backdrop was produced, a century later, the predella now on the altar, depicting the Miracle of the Child Saved from the Flames, the Miracle of Fresh Flowers, given by the Blessed to the children who visited her in her cell, the Funeral of the Blessed followed by Augustinian monks and, finally, the Miracle of the Knight, saved along with his horse from drowning again through the intercession of the Blessed. On this predella there is the coat of arms of a family, once believed to be the Tinolfi family and now ascertained to be the Baldovinetti family, owners of the castle of Lucardo before it passed to the Macchiavelli family, perhaps commissioned in 1486 as a sign of gratitude for the return of the Blessed’s head.

Traditionally attributed to the Cistercian nun Antonia Doni, perhaps the daughter of Paolo Uccello, the predella was returned by Alessandro Bagnoli to the hand of Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi known as lo Scheggia (1406-1486), Masaccio’s brother and renowned woodworker, with a date close to the last years of his activity.

On the altar is a canvas depicting La Beata Giulia in prayer before the Crucifix, after restoration attributed by Bagnoli (2016) to Sienese painter Tiberio Billò. It is a narrative by image of the miracle that took place on January 9th, 1367, when the church bells began to ring to announce the death of the blessed and the people, who rushed to her cell, found her now lifeless, her face cyanotic, praying before a vase of fresh flowers and the Crucifix, identified with the one once in the Church of Santi Tommaso e Prospero and currently in the Church of San Tommaso Apostolo. Originally the two planks of the panel formed the doors of a reliquary cupboard hanging above the altar of the chapel of Beata Giulia, where the veil, the bones and a silver casket with the head were exposed to veneration, reconverted into an altarpiece following the chapel’s renovation patronized in 1581 by Father Ranuccio della Rena, when the bones were reassembled and kept in the urn, now in the cell of the Blessed, located in the compartment under the altar mensa.

Artistic finds and lost works

Lost and Rediscovered Works

In addition to the loss of the Beata Giulia dossal, altars, sepulchres and earthen tombs, works of art of inestimable historical and artistic value were taken from the church in unknown times. Among those lost are the two dossals commissioned in 1366 by Giovanni Boccaccio, one with the Redeemer in the center and at the sides Saints John the Baptist and Mark the Evangelist with the donor, the other with the Madonna and Child and at the sides Saints Miniato and Catherine with the beautiful and delicate Violante, Boccaccio’s daughter. Instead, the two panels mentioned by Neri di Bicci in his “Ricordanze,” a workshop chronicle written by the artist between 1453 and 1475, have been retraced: the first is a Madonna with Saints Jacopo and Andrew, now in the deposits of the Petit Palais in Avignon, begun on March 4th, 1462 for Bastiano d’Andrea da Certaldo; the other, identical in form and size to the previous one, was begun by the artist on August 18, 1463, for Piero di Antonio Lippi and depicts the Coronation of the Virgin with Saints Anthony Abbot, Augustine, the Archangel Raphael with Tobiolus and two musician angels next to the patron, where the space is occupied by a large circle of light with linear rays within which the main group is received, a compositional scheme already adopted by the artist in the version for the Convent of San Salvi completed on December 22th, 1460 and repeated in later years in the panels in the Pinacoteca del Monastero de La Verna, the Museo dell’Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence and the Church of San Giovannino dei Cavalieri in Florence, now at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore.

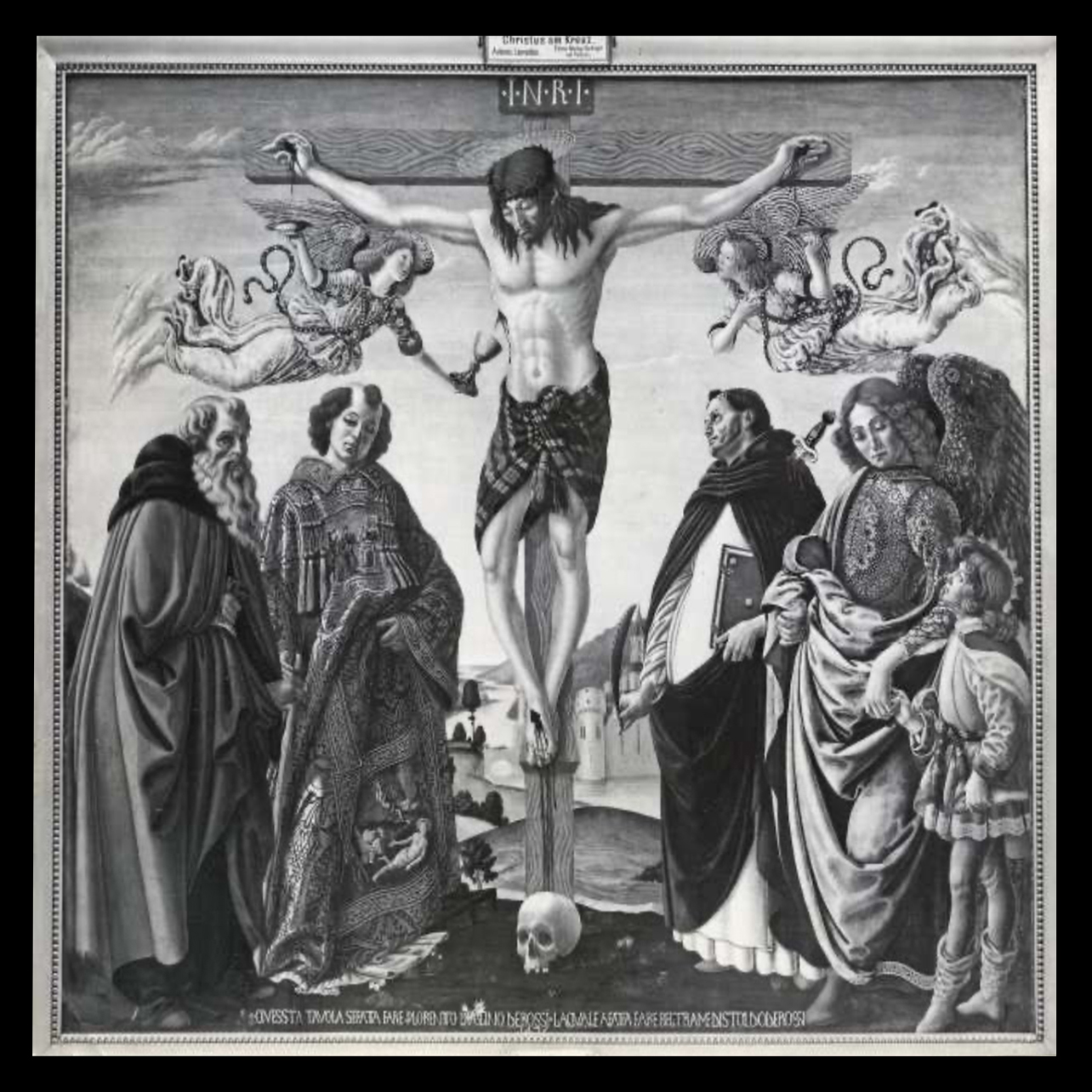

Presumably destroyed by the bombs that fell on the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin in 1945, it is the panel depicting Christ Crucified between Saints Anthony Abbot, Lawrence, Peter Martyr and the Archangel Raphael with Tobiolus, commissioned in 1475 from Francesco Botticini by Beltrame de’ Rossi for the altar of the family chapel in the church, as the original inscription on the archival photos also recalls:

QUESTA TAVOLA S’ E’ FATTA FARE PER LORENTIO D’UGOLINO DE’ ROSSI – LA QUALE A FATTA FARE BELTRAME DI STOLDO DE’ ROSSI.

“This panel was commissioned by Lorenzio d’Ugolino de’ Rossi – it was made by Beltrame di Stoldo de’ Rossi.”

In Certaldo the De’ Rossi family had many farms with cottages and a permanent residence within the castle walls, abandoned by Beltrame in 1480, the year in which he decided to move permanently to Florence, following the fire that destroyed his house causing the death of his brother Lippo.

The family also had since the fourteenth century a family chapel in the basilica of Santo Spirito in Florence, for which Botticini, a pupil and collaborator of Neri di Bicci, had already painted two panels with the Plorant Virgin and St. Augustine, which were transferred to the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence at the time of the Unitarian suppressions.